Considering Risk in Selecting Comparables

Popular Tags

Monday, July 29, 2019 in Education

by Steve Roach, JD, ISA CAPP

As true rarities become harder to find, collectors seem to have an increased tolerance for risk in their purchases. The boldest example of this in recent memory is Christie's 2017 auction of Salvador Mundi, sold by the auction house as a Leonardo da Vinci, for a record-setting $450,312,500. That painting can't seem to stay out of headlines, as scholarly consensus moves away from its full attribution to the artist in favor of a broader attribution to Leonardo and workshop (though some have credited the skillful hand of restorer Dianne Modestini as much as Leonardo in the painting's current presentation).

The $450 million 2017 auction of the Salvador Mundi attributed to Leonardo da Vinci reflects an art market that is increasingly tolerant of risks. Image courtesy of author.

Dealer Robert Simon helped discover the work in 2005 and spent a decade building support for the attribution, solidifying its status as an accepted Leonardo when it was exhibited at London's National Gallery of Art. When it came time to price his Leonardo, Simon faced a challenging situation. As Ben Lewis writes in his recently published book The Last Leonardo, given that there were no relevant auction comparables for Leonardo, or any Old Master painting at this level, Simon considered the 1914 sale of Leonardo's Benois Madonna for $1.5 million and the 1967 purchase by the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. of Ginevra de' Benci for a reported $5 million. Simon applied the Consumer Price Index, finding that both figures became around $34.5 million in 2012. Simon writes, "But if he calculated using relative income and wages, the figure rose to $200 million; and if he used relative output, it became $660 million." With that information, Simon settled on a price target of $125 million to $200 million for his picture. With that information, the $450 million auction price doesn't seem entirely unreasonable.

Increased Appetite for Risk

This taste for risk is seen across collecting categories. For example, take the controversial 1959-D Lincoln cent with the Wheat reverse, rather than the authorized Lincoln Memorial reverse introduced in 1959. Unlike most high-end coins, it was offered uncertified and the "mule" error sold for $60,000 at Ira and Larry Goldberg's June 3 Pre-Long Beach Auction in California. It was graded Mint State 60+ by the auctioneer, since major third-party grading services declined to authenticate it as a genuine U.S. Mint product. Numismatists who have examined the surfaces closely have observed some unusually heavy die polish that is unusual for the period, and the Goldbergs suggested that further research could link it to existing 1958-D and 1959-D cents and confirm the authenticity.

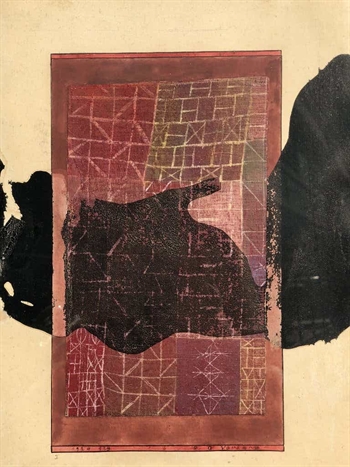

Further research might confirm the authenticity of this 1959-D Lincoln cent with the Wheat reverse used between 1909 and 1958 just like conservation and new restoration techniques might restore this Paul Klee work. Both provide challenges for an appraiser. Image courtesy of Ira and Larry Goldberg Auctioneers.

An unusual piece for sure, but well-heeled collectors are not always averse to some risk when adding coveted items to their collections, as seen with the Leonardo purchase.

A coin dealer friend of mine recently purchased a work by the Swiss modernist artist Paul Klee from a small auctioneer that doesn't normally sell the work of the artist. It was offered in an October 14, 2018, auctioned alongside some other big-name artworks that were found in the storage locker of an art restorer. The collector did his due diligence and confirmed that the work, a gouache and pastel painting on linen titled Vorhang 129 signed by the artist in the upper right corner, was listed and illustrated in the Klee catalog raisonné, a compendium of the artist's works.

It was part of a series of five works where Klee painted on a large piece of linen and subsequently cut in pieces, with "Vorhang" being the German word for curtain. The work was previously offered at Christie's London in 1990 with a low estimate equivalent to $408,000 but did not meet its reserve and went unsold. Then, "sometime after the Christies sale, ink spilled across the middle of the work," and the auctioneer speculated that the work was brought to restorer by an insurance company who wrote it off as a loss.

In its current state it is nearly ruined, and the dealer-collector paid $32,500 for the Klee, meaning that there was a more than 90 percent discount for the damage. The auctioneer conducted tests demonstrating that the ink is water soluble, but the likelihood of getting all the ink out completely is remote. The collector is willing to risk that he can restore it, but appraising this work poses a wide range of questions for the appraiser that would need to be defined in a conversation with the client to determining the intended use of the appraisal, which in turn informs the appraiser's determination of the scope of work.

Hidden Treasures

A few weeks ago Zurich auctioneer Schuler saw a panel painting "in the style" of Florentine Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli soar past its initially modest low estimate of 5,000 CHF (just over $5,000) towards a hammer price of 6,400,000 CHF ($6,563,840) on June 28 after nearly an hour of dogged bidding. The portrait of a young man appears to have come on the market around 1924 where it was published by Wilhelm von Bode as a newly published Botticelli. Later publications were less enthusiastic on its status as an autograph Botticelli and the lot came with a detailed investigation report of the Swiss Institute of Fine Arts which observed, "The technological observations allow the conclusion that it is at the core of a late medieval, respectively early modern panel painting. However, the extensive manipulations in significant parts of the portrayed and a recent restoration after 1961 led to blatant changes that fundamentally disrupt historical authenticity." The report concluded, "The painting has been changed so much by earlier revisions that the original portrait is no longer comprehensible. These revisions may not have been in a restorative sense, but manipulatively, to effect the attribution." One can't evaluate this result without also considering the impact of the Leonardo's sale and how it reflects the market's shifting view of condition when it comes to otherwise prohibitively rare and well-known Old Master artists.

Or, perhaps the buyer of the work attributed to Botticelli was emboldened by the sale of a freshly discovered large painting depicting Judith and Holofernes, which many believe to be either part or fully by the hand of Caravaggio. Set to be auctioned by a French auctioneer on June 27, it sold several days before the auction to American billionaire J. Tomilson Hill for a final price that was "exceptionally more" than the starting bid of $34 million," according to the auction house. If the bold picture gains favor as a genuine Caravaggio in the coming decades, bolstered by future publications and exhibition at significant museums, the price will prove to be a bargain. If it fades from memory and scholarship turns against it, it will be an expensive mistake and a cautionary tale for future generations of collectors.

In each of these scenarios a buyer is willing to take a risk based on a question – that a work was painted by the hand of Leonardo, that coin is a genuine product of the U.S. Mint, that a damaged work can be restored, or that a work is a Caravaggio – for potential long-term value.

What is the appraiser to make of these sales? While most appraisers won't be working with seven-figure Old Master paintings in their day-to-day practice, the case studies are useful to show that pieces with attribution problems, condition problems and even authenticity issues can have a market. The sale of a "Lost Caravaggio" for millions doesn't mean that all paintings attributed to Caravaggio are priced in the millions, just as all not heavily restored Florentine portrait paintings are by Botticelli. The Leonardo and Caravaggio have both made mainstream news, so clients might wonder if they too have a million-dollar old master painting hiding in their attic. While they probably don't, understanding some of the factors underlying unexpected prices can help you explain your role as an appraiser to a client and provide a framework of what you can (and can't) do in the scope of your work.

Steve Roach, JD, ISA CAPP is an appraiser based in Washington, DC, and Baltimore, Maryland. He is a USPAP certified instructor for 7-Hour and 15-Hour USPAP classes, an instructor for ISA's Fine Art course, and is the editor-at-large of Coin World.